Soldier's Watch

MK note: Richard Coate (#36) is the

soldier in the famous "Soldier's Watch" photo.

Here is the photo along with an announcement which, for a while,

was posted under

Dick's entry on Page Five of the Imjin Buddy Bunker:

"TROY

NY - County Executive Henry F. Zwack announced that a public

reception will be held on 14 May 2001 when the Rensselaer County Korean War Memorial

will be featured in the "Photo of the Week" segment during the

History Channel's 8 pm broadcast

of "This Week in History".

US Army

Korean War veteran Richard Coate has accepted an invitation from

County Executive Zwack to attend the event. Mr. Coate is widely

recognized as the veteran in the "Soldier's Watch" image taken by Associated Press

photographer James E. Martenhoff early in March of 1951 for AP

release during the Easter Season, 1951.

A faithful

reproduction of the photograph of the rifleman in silhouette is

etched on the surface of the Rensselaer County Korean War

Memorial,

dedicated in May, 1996, in the city of Troy."

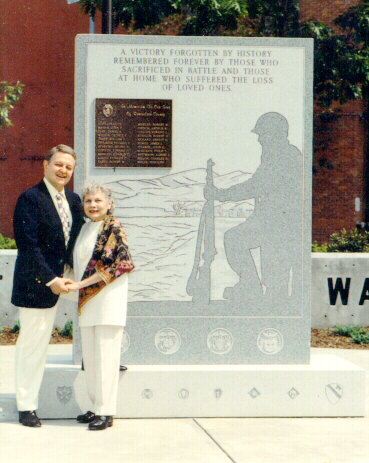

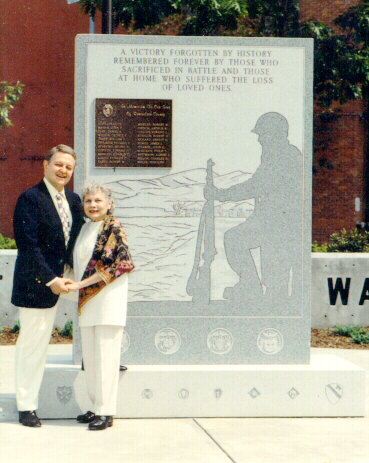

In the

History Channel broadcast, a photo of Richard and Betty Coate at

the Rensselaer

County Korean War Memorial was included also. The narration said: "For

Richard Coate, the image evokes mixed emotions. On the one

hand it evokes the horrors of his days in combat, but it has also

come to symbolize the hope that the veterans of the forgotten war

will no longer be forgotten."

In the

History Channel broadcast, a photo of Richard and Betty Coate at

the Rensselaer

County Korean War Memorial was included also. The narration said: "For

Richard Coate, the image evokes mixed emotions. On the one

hand it evokes the horrors of his days in combat, but it has also

come to symbolize the hope that the veterans of the forgotten war

will no longer be forgotten."

Here

is that photo of Dick and Betty, his wife, taken in

1996 when they attended the dedication of the Rensselaer County Korean War

Memorial.

I am now pleased and

honored to present Richard Coate's (unedited) story that goes with the

Soldier's Watch photo.

MK.

Whenever I am approaching The Rensselaer County Korean War Memorial in

Troy, NY from a promenade overlooking the Hudson (behind City

Hall), I have to pause as the rifleman in silhouette standing in

bold relief on the face of the monument comes into view.

Invariably, I am jettisoned back in time to March 4, 1951 to the

brief chance encounter between two strangers, one an AP

photojournalist, the other a dog-faced, dog-tired rifleman. About

a half hour after first light, the squad to which I was assigned

had just returned from a grueling all-night listening-observation

post in a crater hole down along the banks of the Han opposite

Seoul. Under enemy hands for the second time since the North

Koreans invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950, UN forces were

again preparing for a river crossing to seize the capital city.

The place and timing of the chance encounter between myself and

the AP photojournalist, would become all the more significant in

the ensuing decades.

I remember the specific

place and time I received a batch of letters from home, one of

which contained a newspaper clipping of the AP photograph Betty,

my bride of seven months, received from a compassionate citizen

in Seattle, Wash. I was sitting in a bomb crater hole just off

the MSR in the Western Sector where the 3rd Infantry Division was

moving North to coordinate with an 187th Airborne drop in an

attempted entrapment of a sizable pocket of Chinese pocket of

Chinese entrenched in a valley near Munsan-ni. The 2nd Battalion

of the 15th Infantry Regiment was temporarily stalled in its

tracks and personnel of the entire Battalion lined the MSR in

anticipation of the legendary General Douglas MacArthur's passing

by. It proved to be his second to last visit to the front prior

to his dismissal as Far East Commander. However, I was too

preoccupied reading my mail. I recall munching a chocolate chip

cookie from a batch my mother-in-law had sent while I, hungry for

news from home, read what Betty was receiving for wedding gifts.

So much had happened in the interim that I had completely

forgotten about my encounter with the AP Photographer, so the

news that the photograph was creating quite a stir back in the

States came as quite a surprise. Only when the chatter among the

GIs quieted to a hush did I perk up. "HERE HE COMES!"

After catching a brief glimpse of the legendary General's profile

as his command jeep breezed by, I returned to the crater hole to

resume reading Betty's account of how she and my mother were

receiving news paper clipping of the photo from all over the

States. And in my response I informed her of my "gentle

amusement at all the fuss."

By the time I rotated

home, almost a year later, I had completely forgotten about the

photograph. When Betty brought the newspaper clipping out and

displayed them on the kitchen table at her home in Trenton, OH. I

stood there speechless. Though the front page of the March 12th,

1951 edition of the Los Angeles Times was impressive, the

clipping of Spokesman Review, Spokane, Washington really stunned

me. It read, "Silhouette of Yank Rifleman symbolizes

fighting forces in Korea." Little could we have known that

it was a precursor of things to come. The photo was published in

our hometown newspaper, The Middletown Journal, Middletown, Ohio,

on Easter Sunday of '51, accompanied by a Journal reporter's

interview of Betty. Recognizing the archival value of the photo,

for the family at least, she contacted AP requesting a glossy. AP

responded by forwarding one along with an AP release through the

Middletown Journal. When I examined the AP release I noted that

the photographer's initials were "JM". He would remain

a mystery man for the better part of five decades.

37 years later, Betty

would again startle me when she displayed on our bed the full

page advertisement in the October 9, 1989 edition of The New York

Times. When I entered the bedroom that afternoon I stopped in my

tracks. The bold print read, "THE KOREAN WAR ISN'T OVER."

However, when I read the first sentence of the narrative in small

print at the bottom of the page I knew why she had chosen to

surprise me. The first sentence read, "The guns fell silent

over 36 years ago. Sports are now played on grass-carpeted fields

where battles once raged." When we watched the 1988 Olympic

Games held in Seoul, I realized that the house in which the

photograph was taken in early March of '51 was in the environs of

what would become the turf for the Olympic Stadium. But the next

line was even more edifying. "But in America, no war is

really over until a memorial is raised to honor the men and women

who risked their lives for our country." Though twenty four

years had lapsed since it was used as the linchpin of the USO

fund drive as a symbol of America's fighting forces throughout

the globe, it was all the more relevant a symbol in the fall of

1989. In '65, the Korean War was, by most Americans, still deemed

the first war that America lost. But in '88, the Olympic Games in

Seoul had demonstrated to the world that South Korea was now a

ranking member of the free, capitalist nations in the world, a

modern Democracy and a thriving center of international commerce.

When I contacted the

fund HQ in Arlington, I spoke to a woman by the name of Jan

Jackson who identified herself as General Stilwell's Executive

Assistant. I requested permission to quote from the NY Times

advertisement for a story I was writing. She informed me that

General Stilwell was the Chairman of the Presidential Advisory

Board for the design of the memorial as well a head of the fund

drive and former Commander of UN troops in Korea, I was not a

little intimidated. Nevertheless, the former Corporal in Co E, 15th

Inf Rgt, 3rd Inf Div, who had (and still has) a penchant for

borrowing words from Shakespeare, screwed

his courage to the sticking point and told

her some of his story. She exclaimed, "By all means!"

Forwarding a copy of

The Unidentified Soldier in the USO Poster story to

Ms. Jackson, I requested that she present it to General Stilwell.

When the general read my account of the vow I had made while

performing my duties as "E" Company Clerk at the 2nd

Battalion, 15th Infantry Regiment, aid station during the action

on Hills 487-460, he was obviously impressed with my assertion

that "combat veterans do not take their vows lightly."

Standing beside the corpse of a buddy from Brooklyn, NY, one

among the field of dead heroes beside the Battalion Aid station,

I had vowed that I would conduct my life so as to be worthy of

survival. As they had made a difference in the way they died, I

would make a difference in the way I lived. Clearly, the general

knew that I had my vow in mind when I, in May of 1952, while

still in the army, wrote a letter to Life Magazine expressing my

moral outrage about "the forgotten war of Korea". Given

that the horrors I shared with the medical staff at that

Battalion Aid station was a defining moment in my life, that vow

is still strongly associated with photo of the lonely rifleman in

silhouette standing watch in what I referred to as "the

forgotten war". A month after I wrote the letter, I was

transferred from active duty to reserve status. Fourteen months

would lapse before the truce signing. During that time I became

all the more aware of the apathy and indifference on the part of

the American people toward the mounting casualty count on the

Korean peninsula. I would be reminded of my vow again when, in

December of '64 through the spring of '65, the photo was again

published on a nationwide basis, this time as the linchpin of the USO fund drive, symbolizing American fighting forces throughout

the globe; and, in the last paragraph of his letter to me, dated

27 Dec 1989, General Stilwell wrote, "I salute your courage;

I admire your initiative ..." in order to acknowledge the

significance of that defining moment in my life. Recognizing the

symbolism of the photograph, he also realized the story I

associate with it could be used for the fund drive. His letter of

commendation empowered me to act upon my vow, changing the course

of my life in the process. "The true value of your work,"

he wrote, "will be measured by those who were there, men who

can really appreciate the pain of an author valorous enough to

experience it all again and again for the benefit of others."

General Stilwell's letter became central to my pro bono press packets targeting

some of the more prestigious newspaper and magazine editors in the States.

Naturally I wondered if the AP photojournalist was still among the living. By

the same token I wondered if he knew his subject had survived the war. My wife,

Betty and I had reason to be proud. But for our efforts, the photograph was in

national circulation for the third time in its history, well on the way to

attaining a unique place as a photojournalistic icon of the Cold War. Over a

year and a half lapsed since General Stilwell read my story, The Unidentified

Soldier in the USO Poster, when I decided to determine the identity of the

mystery man. Late spring of '91, when I made inquiries at World Wide Photos in

the AP library in Manhattan, an elderly woman in the office responded to my

query on the identity of the initials "JM" on the copy of the AP release I

handed to her. "Why that's Jimmy Martenhoff!" she exclaimed.

I learned that he left AP in '57 and nobody in the office knew of his

whereabouts or whether he was still among the living. I was granted permission

to examine the Martenhoff file photos. I was in all of the four photos he took

that morning, two of which were the rifleman in silhouette. Neither the group

shot of the platoon gathered around the fire or the one of me and a buddy

"coming off patrol" or either of the two silhouettes of me were in the file. Nor

was there a record of the one AP published under the label "Korean Watch" ever

having been there. I could only conclude that it was removed in 1964 when the

advertising agency representing the USO introduced it as the linchpin of their

fund drive. Though I discovered other photographs he had taken of riflemen in

silhouette at other sites, unlike me, none were identified. Among those was that

of a soldier with his back to the camera, probably taken shortly after

Martenhoff departed from our assembly point. That rifleman had obviously been

singled out to pose at the crest of a hill overlooking 3rd Infantry Division HQ

in a tent city in the valley below, the Han River in the background. His back to

the camera, his silhouette was used to anchor the shot. Unnamed and

unrecognizable, his identity is lost to posterity. I wondered if he had survived

the war.

Once he placed me in the door frame of the war gutted thatched roof house, the

photographer backed off to kneel and frame me within his lens. He did not know

that I had a number of impressive acting credits in Ohio State Theater

Department productions and professional TV credits as well. With three years of

WOSU radio broadcasts under my belt, I been inducted into the prestigious

Professional Broadcasting Fraternity, Alpha Epsilon Rho. A photography buff

prior to induction, I fully understood the impact of a silhouette against bright

light. Bone tired, I rose to the occasion by striking what I thought was a

suitable dramatic pose. Planting my foot on the door sill I thrust the rifle

forward and placed its butt on the sill as well. Obviously pleased with what he

saw, he adjusted both his position and focus before clicking the shutter. For

the second shot of the same pose, my gaze was directed more toward the distant

hills. With that he nodded and smiled. A man of few words, I took it to mean an

expression of satisfaction. Apparently in a rush to get to move on to another

site while the day was still young, he left the interior of the house with nary

a word. About to drop on a pile of straw for a snatch of shut eye, I realized

the photographer had failed to take my name and address. Were one of the two

solo shots of me ever published, Betty would have no way knowing that the

soldier enshrouded in shadow was her husband. Racing out of the house, I caught

the photojournalist before he and his colleague departed in their jeep. Without

so much as an apology for the oversight, he removed a pad and pencil from the

pocket of his field jacket, jotted down my name and address. When asked if he

thought any of them would be published he replied, "Probably one of the

silhouettes." A combat soldier sweats the odds against survival on a daily

basis. Though I desperately wanted to return home to my bride, I knew I had

little or no control over the circumstances in which I found myself. In the

event that an enemy bullet with my name on it terminated my life, that photo

with my name on it would mean a hell of a lot to her and all our folks back

home.

When I awakened from a brief nap, it was as if this chance encounter was but a

dream in which I was an actor playing a role. For it seemed like an interlude

between the acts of an unfinished drama; and in that brief interval I was able

to exercise a degree of control over the circumstance in which I found myself.

As an actor, the door frame in which I performed was not unlike the proscenium

arch of a stage which, in theatrical terms, is referred to as "the fourth wall"

separating the actors from the audience "out front." In my ruminations, the

photographer was but a member of that audience. Brief as it was, despite my

physical and emotional exhaustion, for I had gone twenty four hours without

sleep, I had succeeded in using my training and instinct as an actor. Decades

later I would more fully appreciate my performance, my creative contribution to

what became a classic example of photo journalistic art, destined to have

lasting impact.

Shortly after I learned the identity of the mystery man I changed the photo

credit from AP to AP James E. Martenhoff. However, I was acutely aware that my

identity, like the soldier on the crest of the hill overlooking 3rd Infantry

Division HQ would have been lost to posterity had I not caught the

photojournalist in the nick of time prior to his departure from our assembly

point. As late as '97, when an article I had written for "The Graybeards," the

KWVA newsletter, was published, Martenhoff learned of the impact that his

photograph was again making, some 24 years after its nationwide release on USO

Public Service Advertisements. When I finally contacted the mystery man who had

made such a tremendous impact upon my life, I was eager for his response. If he

was pleased, he didn't say so. Friendly as our phone conversation was, I

reminded him that I had to ask that the name and address of his subject be

included if the photo was published. During our chat, I learned that Martenhoff

did not retain a copy of the photograph. Had I not been identified Betty, way

back in March of '51, would have had no reason to contact AP. But for her

initiative, my wife and I were the only people in the world who still retained

both a glossy of the photo and the AP release which identified not only the

photographer as "JM" but his subject.

Though she knew it had archival value for the family, she had no way of knowing

that she was preserving an important part of Martenhoff's legacy. It is not

without irony that our successful reintroduction of the AP photo labeled "Korean

Watch" in its first national release, permitted me to fulfill the vow I made

beside the body of a fallen comrade, one among a field of dead heroes who were

Killed in Action during the battles for Hills 487-477. Martenhoff's genius in

capturing the evanescent dawning light fringing the silhouette in that "fourth

wall" enhanced the power of its statement. Shakespeare said it best: "All the

world's a stage and all the men and women merely players: They have their exits

and their entrances; And one man in his time plays many parts." For me the photo

embodies a personal metaphor; I survived the war to play many parts, in theater

and in real life and the photo has stood the test of time.

3rd

Division Page

3rd

Division Page

IBB

Map and Photo Index

IBB

Map and Photo Index

IBB

- Page Five Foxholes and Choppers

IBB

- Page Five Foxholes and Choppers

"Can

Do" Photo Index

"Can

Do" Photo Index

In the

History Channel broadcast, a photo of Richard and Betty Coate at

the Rensselaer

County Korean War Memorial was included also. The narration said: "For

Richard Coate, the image evokes mixed emotions. On the one

hand it evokes the horrors of his days in combat, but it has also

come to symbolize the hope that the veterans of the forgotten war

will no longer be forgotten."

In the

History Channel broadcast, a photo of Richard and Betty Coate at

the Rensselaer

County Korean War Memorial was included also. The narration said: "For

Richard Coate, the image evokes mixed emotions. On the one

hand it evokes the horrors of his days in combat, but it has also

come to symbolize the hope that the veterans of the forgotten war

will no longer be forgotten."